Ultimo aggiornamento 2021-04-08 15:20:20

Nella terapia della sterilità, molti fattori negativi (impervietà tubarica in primis, ostilità cervicale, disovulazione e dispermia) sono stati superati con le tecniche IVF-ET ed ICSI che permettono di by-passare i problemi tubarici e cervicale e ottenere embrioni di buona qualità nel 95% dei casi ma con tassi di gravidanza del 12-25% per ciclo di trattamento (1-3). La bassa percentuale di gravidanza è dovuto al fallimento dell’impianto che attualmente è il principale problema su cui discutere. Nella gestione delle tecniche PMA,  per aumentare l’outcome gravidico si è puntato sul miglioramento della qualità embrionale, recettività endometriale e sincronizzazione fra transfer embrionale e maturità endometriale adeguata (endometrio “in fase”). Recentemente si è introdotto il concetto di trasferimenti “omogenei” (“homogeneous transfers”, HT), in cui il trasferimento omogeneo è definito come il trasferimento di embrioni con una morfologia simile (1-4).

per aumentare l’outcome gravidico si è puntato sul miglioramento della qualità embrionale, recettività endometriale e sincronizzazione fra transfer embrionale e maturità endometriale adeguata (endometrio “in fase”). Recentemente si è introdotto il concetto di trasferimenti “omogenei” (“homogeneous transfers”, HT), in cui il trasferimento omogeneo è definito come il trasferimento di embrioni con una morfologia simile (1-4).

Qualità embrionale: molti progressi sono stati ottenuti nei centri PMA per ottimizzare il pregnancy rate migliorando la qualità embrionale e scegliendo gli embrioni di migliore qualità.

Anche se non esiste una regola fissa e uguale per tutte le pazienti, è opinione diffusa che il transfer al 5-6° giorno, allo stadio di blastula, sembra aumentare l’outcome gravidico per diversi motivi: gli embrioni con patologie genetiche non si sviluppano oltre il 5° giorno e quindi si assiste ad una spontanea selezione embrionale che può essere ulteriormente raffinata mediante PGD (Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis) (29-33). Inoltre al 5-6° giorno l’endometrio è altamente ricettivo, sicuramente più che al 3° giorno, ed infine la possibilità di migliorare l’attecchimento mediante hatching della zona pellucida che non può essere effettuata su embrioni a 2-4 cellule (5-14).

La percentuale di aborto ovulare è più elevato dopo il trasferimento di embrioni a 2-4 cellule rispetto agli embrioni allo stadio di ≥8 cellule ed è significativamente aumentato quando l’embrione presenta >20% di blastomeri frammentati mentre diminuisce significativamente in caso di embrioni con precoce primo cleavage che risulta essere il migliore indicatore di qualità embrionale nelle tecniche IVF (15-20). La frammentazione blastomerica è da valutare, al microscopio invertito a ingrandimento 400X, 44 ± 2 h dopo l’inseminazione o la microinezione. La frammentazione blastomerica è stata valutata come segue: A = nessuna frammentazione; B = 1-20% in volume di frammenti anucleati; C = 21-50% in volume di frammenti anucleati; e D = >50% in volume di frammenti anucleati (21-28).

Ovviamente la scelta di effettuare il transfer al 5-6° giorno dipende anche dall’età della paziente, dalla sua storia clinica, dal numero di embrioni ottenuti e dalla sincronia con la maturazione endometriale (29-30).

Recettività endometriale: la bassa percentuale gravidanze in evoluzione (25%) rispetto al numero di embrioni ottenuti è da addebitare a numerosi fattori come la presenza di idro- e sacto-salpinge, infezioni pelviche, PID, obesità, diabete mellito, cardiopatie, fattori immunologici e fattori psico-somatici, ma è la recettività endometriale tout-court il principale fattore limitante il successo delle tecniche PMA, il cul de sac in cui vanno ad restringersi le probabilità di successo delle tecniche ART (10-14).

L’endometrio esprime una finestra di recettività fra il 15° e il 19° giorno di un ciclo spontaneo e dal 4° al 9° giorno dopo il picco LH o somministrazione di HCG dei cicli stimolati. Moderne tecniche hanno permesso di individuare esattamente la finestra di recettività in cicli non stimolati in modo da ottimizzare il transfer embrionale in caso di ovodonazione e nei casi di embryo-transfer differiti (15-17). La finestra di impianto è correlata a modificazioni morfologiche endometriali, modificazioni ormonali e biochimiche, modificazioni recettoriali, secrezioni di citochine e prostaglandine in un insieme armonico e strettamente collegato (18-29).

Modificazioni morfologiche (decidualizzazione):

- L’epitelio superficiale si ripiega e le cellule si distendono e mostrano un citoplasma più chiaro, alcune cellule sviluppano nuclei grossi ed ipercromici-poliploidi.

- Le ghiandole endometriali subiscono un fenomeno di Iperplasia morfologica e funzionale.

- Le cellule stromali si decidualizzano passando da una conformazione affusolata o a stella ad una forma globosa, rotondeggiante, aumento di volume, accumulo citoplasmatico di glicogeno e granuli lipidici.

- neo-angiogenesi e congestione dei sinusoidi vascolari

- in caso di gravidanza iniziale, anche extra-uterina, a carico delle cellule epiteliali secretive delle ghiandole endometriali, si osservano particolari modificazioni (fenomeno di Arias-Stella) dovute all’azione dell’HCG.

- comparsa di integrine, MMP (Matrix Metallo-Proteinasi): Collagenasi, Gelatinasi e Stromelisine, enzimi litici di origine endometriale e fibronectina di orgine embrionale, che favoriscono l’annidamento.

- prostaglandine intracellulari PGF2α, PGE2, PGI2 e PGD2

- La prolattina: è prodotta soprattutto nella fase luteale tardiva; a basse concentrazioni risulta essere luteotrofica, mentre a dosi elevate è luteolitica (30-33).

Citochine e fattori di crescita: la complessità degli eventi di impianto e placentazione è resa evidente dall’elevato numero e dalla varietà delle citochine e dei fattori di crescita espressi dalle cellule stromali e ghiandolari in fase luteale e soprattutto durante la “finestra di impianto” ed implicati in questi processi. Alcuni sono fondamentali, altri non sono indispensabili. I difetti di espressione e azione di queste citochine e fattori di crescita provocano diminuzione della recettività endometriale e il fallimento o diminuzione delle percentuali di impianto. Di notevole importanza risultano i membri della famiglia gp130 come l’interleuchina-11 (IL-11) e il fattore di inibizione della leucemia (LIF), la superfamiglia del fattore di crescita di trasformazione beta (TGFbeta), incluse le attivine, i fattori stimolanti colonia (CSF), le interleuchine IL-1 e IL-15. Nuovi dati stanno emergendo anche per il ruolo di una serie di chemiochine (citochine chemioattrattive) sia nel richiamo di specifici leucociti nei siti di impianto che nella differenziazione dello stroma endometriale (34-47).

- LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor): è una leuchina della classe IL-6 che inibisce la differenziazione cellulare. E’ stato dimostrato che la LIF, regolata dalla proteina p53, agevola l’impianto nel modello del topo e probabilmente negli esseri umani (56). La LIF umana ricombinante potrebbe contribuire a migliorare il tasso di impianto nelle donne con infertilità inspiegata (57). LIF è normalmente espressa nel trofectoderma dell’embrione in via di sviluppo mentre il suo recettore LIFR è espresso in tutta la massa cellulare interna (58,59).

- IL-11 (Interleuchina-11): citochina appartiene alla famiglia dell’interleuchina 6 e del LIF. La sua secrezione dalle cellule stromali avviene soprattutto nella fase luteale tardiva ed è stimolata dal progesterone con il concorso di diversi fattori di crescita. IL-11 promuove la sintesi delle proteine implicate nei processi flogistici e promuove la proliferazione locale di linfociti. E’ perciò direttamente interessata nella immunologia della gravidanza (60-66). Il difetto di secrezione locale di IL-11 comporta una difettosa differenziazione delle cellule stromali e conseguente deficit di impianto (67-74)

- IL-6 (Interleuchina-6)

- HBEGF, Heparin Binding Epidermal Growth Factor

- Colony Stimulating Factor-1

- IGF-I, fattore di crescita insulino-simile

- EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor): è un fattore di crescita che svolge un ruolo importante nel regolare la crescita, la proliferazione e la differenziazione cellulari, legandosi al suo recettore EGFR. Scoperta del premio Nobel Stanley Cohen nel 1986. Poiché l’iperespressione di EGF è un momento fondamentale per l’innesco e lo sviluppo di alcune neoplasie, la sua inibizione può in qualche modo interrompere la carcinogenesi (48). A questo scopo, sono state sviluppate alcune terapie basate su farmaci biotecnologici e anticorpi monoclonali; alcuni di questi ultimi sono diretti verso il recettore del fattore di crescita dell’epidermide, portando alla sua inattivazione e conseguente inibizione della proliferazione cellulare (49-52). La funzione dell’EGF nel processo di decidualizzazione sembra indirizzata all’epressione del fattore tissutale (TF) che rappresenta il fattore primario di emostasi per prevenire l’emorragia peri-impianto nella zona delle cellule stromali endometriali perivascolari (HESCs) durante l’invasione trofoblastica endovascolare. Per l’espressione dell’EGF contribuiscono sia l’azione del progesterone che dell’estradiolo, anche se quest’ultima non è indispensabile (52-55).

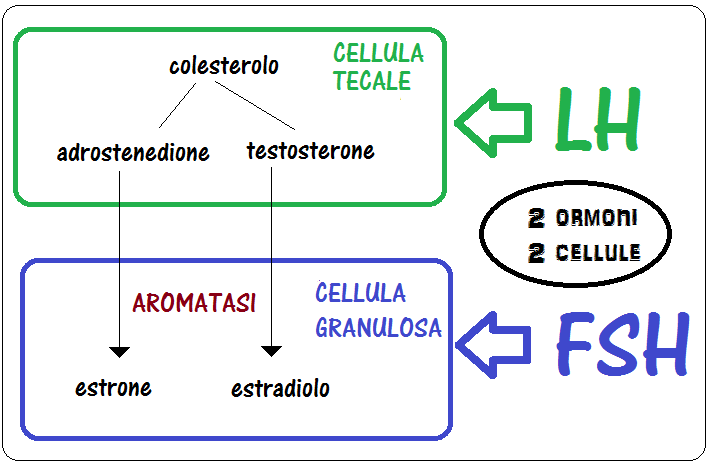

- Estradiolo e progesterone: la maturazione endometriale è l’ultima tappa di un lungo processo che può essere riassunto in una fase di rigenerazione endometriale indotta dall’estradiolo e in unafase di maturazione endometriale o decidualizzazione indotta dal progesterone. Il progesterone viene fisologicamente prodotto prevalentemente dal corpo luteo fino a circa 8 settimane di amenorrea gravidica quando la sua produzione è di fatto sostituita da quella del trofoblasto placentare.

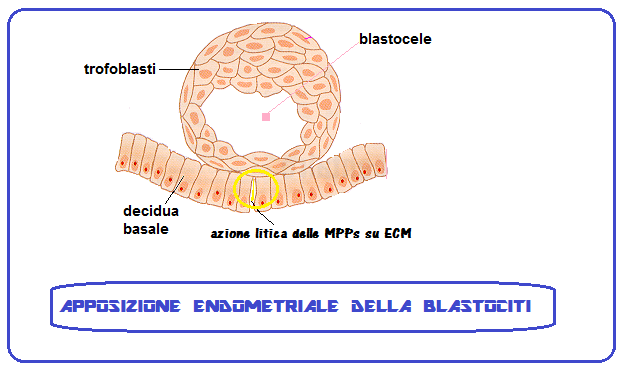

Fecondazione e annidamento: Nel ciclo spontaneo, la fecondazione dell’ovocita avviene nel terzo distale tubarico. L’embrione e schematicamente può è trasportato dal movimento delle cilia epiteliali tubariche verso la cavità uterina. Durante la migrazione lo zigote moltiplica il numero dei suoi blastomeri e si trasforma in morula al 3° giorno circa. Al 7° giorno dopo la fecondazione, l’embrione giunge in cavità uterina allo stadio di blastocisti. Se l’ovulo fecondato giungesse in utero prima della sua trasformazione in blastocisti avrebbe maggiori difficoltà ad impiantarsi anche perchè rischierebbe di trovare un endometrio non recettivo.

La blastocisti rimane sospesa nel liquido della cavità uterina per 2-3 giorni mentre si libera della zona pellucida che avvolge l’embrione e ne impedisce l’annidamento tubarico (GEU). In questo periodo inoltre si sviluppa la porzione del foglietto trofoblastico prossimo alla decidua che si duplica in uno strato esterno detto sinciziotrofoblasto e in uno strato interno denominato citotrofoblasto. Questa è la fase in cui ha inizio l’annidamento vero e proprio.

L’annidamento endometriale dell’embrione è reso possibile dall’azione litica di enzimi, come la L-selectina, e la Matrix Metallo-proteinasi (MMP) detta anche matricina. Le principali classi di MMP sono le Collagenasi, le gelatinasi e le Stromelisine. Questi enzimi esercitano un’azione litica sulle cellule superficiali endometriali e, soprattutto, su integrine e matrice extra-cellulare (ECM). Le integrine sono glicoproteine transmembrana che uniscono le che collegano le proteine della matrice extracellulare ai microfilamenti intracitoplasmatici costituendo un ponte che rende stabile il rapporto delle cellule con il tessuto extracellulare (ECM) e permette la trasmissione dei segnali intercellulari. Nell’endometrio sono presenti 22 tipi di integrine, mentre nell’embrione è presente l’integrina chiamata fibronectina. Inoltre la porzione extra-cellulare delle integrine è provvista di 6 siti di legame (ligandi) che si agganciano ai ligandi embrionali in un’azione sinergica ed in tal modo le integrine sono in grado di mediare, “guidare” l’adesione della blastocisti all’endometrio. Inoltre le MMP stimolano l’angiogenesi: favorendo la migrazione delle cellule endoteliali e la formazione della struttura dei capillari grazie al rilascio di fattori di crescita angiogenici dalla matrice extracellulare. Inoltre sono provviste di azione opposta inibente la neoangiogenesi mediante fattori inibitori in un complesso gioco di equilibrio fondamentale nello sviluppo placentare come nello sviluppo dei processi neoplastici che includono molteplici pathways (22-33).

Il sinciziotrofoblasto prolifera e penetra nella parete uterina (per circa 1/3 della parete uterina), abitualmente a livello del fondo dell’utero (zona in cui il miometrio è meno tonico), più raramente sulla parete posteriore o anteriore, Al 14º giorno dopo la fecondazione dell’ovocita, la blastocisti è totalmente incorporata nello stroma dell’endometrio. In questa fase l’endometrio, sotto lo stimolo del progesterone, è in trasformazione deciduale: diventa iperplastico e le ghiandole aumentano di numero e di volume e secernono un liquido ricco di glicogeno e lipidi che forniranno nutrimento all’eventuale impianto della blastocisti (34-39).

A processo compiuto (25° giorno del ciclo, poco dopo l’eventuale annidamento dell’embrione) l’endometrio si presenterà con uno strato superficiale (la decidua), situata immediatamente al di sotto dell’epitelio di rivestimento dell’endometrio, ed uno strato profondo (stroma) di consistenza spongiosa dovuta alle numerose ghiandole ripiene di liquido secretivo (40-42).

Endocrinologia della maturazione endometriale: la rigenerazione endometriale è indotta dall’estradiolo secreto dalle cellule della granulosa su induzione del FSH mentre la maturazione endometriale, la trasformazione deciduale, è governata dal progesterone secreto dal corpo luteo sotto stimolo dell’LH (43-44).

A differenza di questa visione convenzionale, recenti studi hanno suggerito che, oltre ai suoi effetti indiretti mediati dalla secrezione steroidea ovarica, l’LH può agire anche con azione diretta sull’endometrio sia nella fase follicolare che nella fase luteale (45-49).

La risposta delle cellule-bersaglio alle gonadotropine é facilitata dalle prostaglandine intracellulari PGF2α, PGE2, PGI2 e PGD2, dal fattore insulino-simile IGF-I, EGF e dal calcio. La prolattina a basse concentrazioni risulta essere luteotrofica, mentre a dosi elevate è luteolitica (50).

- Valutazione ecografica thikness endometriale e IUS: Uno spessore endometriale <5 mm si osserva di solito nella prima parte della fase follicolare fino a raggiungere i 10-14 mm circa a metà di questa per mantenersi su valori di 12-13 mm fino al 28° giorno di un ciclo spontaneo. La forma dello spessore endometriale (IUS, Intra Uterine Signal) varia anch’esso durante il ciclo variando da un’immagine lineare in fase follicolare precoce a una trilineare in epoca pre-ovulatoria a un’immagine ovoidale e compatta come un occhio di bue (eye’s bull) in fase luteale. Un thikness <6 mm non è compatibile con l’instaurarsi di una gravidanza.

- Profilo LH: si è ritrovato che la presenza di numerosi picchi di LH sono associati in modo statisticamente significativo con la presenza di piccoli follicoli in crescita e non aspirati. Tali picchi si presentano di ampiezza minore rispetto al normale surge di LH dei cicli spontanei e sono associati a rialzi dell’estradiolo pre-ovulatorio anch’essi inferiori e corpi lutei di dimensioni ridotte. In questi casi l’esame istologico dell’endometrio rivela una netta asincronia di maturazione fra mucosa e stroma dell’endometrio con ridotto outcome gravidico. Quindi i protocolli di stimolazione ovarica nei cicli di fecondazione in vitro dovrebbero essere programmati in modo da ottenere un singolo, unico, elevato picco di LH e l’eliminazione di ulteriori picchi di LH.

- Datazione istologica secondo i criteri di Noyes: risale a molti anni fa (1975) ed è ancora oggi la più utilizzata. Le mutazioni morfologiche presenti nella prima settimana dopo l’ovulazione si manifestano inizialmente nella componente ghiandolare (mitosi, vacuolizzazione basale e secrezione) successivamente nelle variazioni stromali (edema, reazione predeciduale e infiltrazione leucocitaria). Si definisce “in fase” quando i dati istologici corrispondono alla fase del ciclo con una variazione non superiore a 2 giorni.

- ERA test: la valutazione di Noyes, sebbene utile per differenziare l’endometrio proliferativo da quello secretivo, non permette di individuare con certezza quei cambiamenti dell’endometrio che coincidono con l’acquisizione della recettività alla blastocisti. Con lo sviluppo della tecnologia “microarray” è stato possibile valutare l’espressione genica dell’endometrio umano nelle varie fasi, compresa quella di recettività. Il test di recettività endometriale, ERA Test, è un metodo sviluppato da IVIOMICS dopo decenni di ricerca e permette di trasferire gli embrioni nel periodo di massima recettività endometriale. Questa tecnica consente di valutare lo stato di recettività dell’endometrio mediante una biopsia endometriale effettuata dopo 7 giorni dal picco di LH in cicli precedenti all’embryo transfer sia su ciclo spontaneo che dopo preparazione artificiale dell’endometrio con estrogeni e progestinici. La finestra d’impianto non cambia tra un ciclo e l’altro per un periodo relativamente lungo della vita riproduttiva. Sul materiale prelevato si analizza l’espressione di 238 geni coinvolti nella recettività dell’endometrio. Se l’endometrio è recettivo significa che la finestra d’impianto corrisponde al periodo in cui è stata effettuata la biopsia. Se non è recettivo è possibile che la finestra d’impianto sia spostata in avanti, quindi il prelievo va ripetuto in un ciclo successivo circa due giorni più tardi rispetto alla precedente biopsia. Non è attendibile per la valutazione della finestra d’impianto in cicli stimolati, per l’interferenza dovuta all’assunzione di ormoni.

.

PRESIDI TERAPEUTICI:

- Blastocisti: permette di poter sincronizzare in modo ottimale la maturazione endometriale e lo sviluppo embrionale

- Embryo-transfer ecoguidato

- Assisted zona hatching

- Biopsia pre-embrionale (Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis, PGD): consente di utilizzare solo embrioni senza alterazioni genetiche e perciò dotati di maggiore vitalità.

- Immunoglobuline aspecifiche endovena: per contrastare le infezioni endometriali sub-cliniche.

- “Local injury: la revisione cavitaria strumentale e la biopsia endometriale effettuata nel ciclo precedente alla stimolazione ovarica per IVF sembra migliorare le percentuali di impianto nelle donne con fallimento dell’impianto ripetuto ed inspiegato.

References:

- Margalioth, E., Ben-Chetrit, A., Gal, M., Eldar-Geva, T. Investigation and treatment of repeated implantation failure following IVF-ET. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3036–3043.

- Simon, A., Laufer, N. Repeated implantation failure: clinical approach. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1039–1043.

- Boivin, J., Bunting, L., Collins, J.A., Nygren, K.G. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1506–1512.

- Moura-Ramos, M., Gameiro, S., Canavarro, M.C., Soares, I. Assessing infertility stress: re-examining the factor structure of the Fertility Problem Inventory. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:496–505.

- .Shapiro, B.S., Daneshmand, S.T., Garner, F.C., Aguirre, M., Ross, R. Contrasting patterns in in vitro fertilization pregnancy rates among fresh autologous, fresh oocyte donor, and cryopreserved cycles with the use of day 5 or day 6 blastocysts may reflect differences in embryo-endometrium synchrony. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:20–26.

- Franasiak, J., Forman, E., Hong, K., Werner, M., Upham, K., Scott, R. Investigating the impact of the timing of blastulation on implantation: active management of embryo-endometrial synchrony increases implantation rates. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:S97.

- Forman, E., Franasiak, J., Hong, K., Scott, R. Late expanding euploid embryos that are cryopreserved (CRYO) with subsequent synchronous transfer have high sustained implantation rates (SIR) similar to fresh normally blastulating euploid embryos. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:S99.

- Barrenetxea, G., de Larruzea, A.L., Ganzabal, T., Jiménez, R., Carbonero, K., Mandiola, M. Blastocyst culture after repeated failure of cleavage-stage embryo transfers: a comparison of day 5 and day 6 transfers. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:49–53.

- Ruiz-Alonso, M., Galindo, N., Pellicer, A., Simon, C. What a difference two days make: “personalized” embryo transfer (pET) paradigm: a case report and pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:1244–1247.

- T., Klentzeris, L., Barratt, C., Warren, M., Cooke, S., Cooke, I. A study of endometrial morphology in women who failed to conceive in a donor insemination programme. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:935–938.

- Navot, D., Scott, R.T., Droesch, K., Veeck, L.L., Liu, H.-C., Rosenwaks, Z. The window of embryo transfer and the efficiency of human conception in vitro. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:114–118.

- Wilcox, A.J., Baird, D.D., Weinberg, C.R. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1796–1799.

- Tapia, A., Gangi, L.M., Zegers-Hochschild, F., Balmaceda, J., Pommer, R., Trejo, L. et al, Differences in the endometrial transcript profile during the receptive period between women who were refractory to implantation and those who achieved pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:340–351.

- Ruiz-Alonso, M., Blesa, D., Díaz-Gimeno, P., Gómez, E., Fernández-Sánchez, M., Carranza, F. et al, The endometrial receptivity array for diagnosis and personalized embryo transfer as a treatment for patients with repeated implantation failure. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:818–824.

- Klein J, Sauer MV 2002 Oocyte donation. Best Practice and Research in Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 16, 277–291.

- Ziebe S, Petersen K, Lindenberg S, Andersen AG, Gabrielsen A, Andersen AN. Embryo morphology or cleavage stage: how to select the best embryos for transfer after in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1545–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.7.1545.

- Hourvitz A, Lerner-Geva L, Elizur SE, Baum M, Levron J, David B, Meirow D, Yaron R, Dor J. Role of embryo quality in predicting early pregnancy loss following assisted reproductive technology. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;13:504–9. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60637-2.

- Van Blerkom J, Davis P, Alexander S. A microscopic and biochemical study of fragmentation phenotypes in stage-appropriate human embryos. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:719–29. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.4.719.

- Hardarson T, Hanson C, Sjogren A, Lundin K. Human embryos with unevenly sized blastomeres have lower pregnancy and implantation rates: indications for aneuploidy and multinucleation. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:313–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.2.313

- Magli MC, Gianaroli L, Ferraretti AP. Chromosomal abnormalities in embryos. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;22(183 Suppl 1):S29–34. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00574-3.

- Plachot M, Junca AM, Mandelbaum J, de Grouchy J, Salat-Baroux J, Cohen J. Chromosome investigations in early life. II. Human preimplantation embryos. Hum Reprod. 1987;2:29–35.

- Wells D, Bermudez MG, Steuerwald N, Malter HE, Thornhill AR, Cohen J. Association of abnormal morphology and altered gene expression in human preimplantation embryos. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:343–55. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.143.

- Jurisicova A, Antenos M, Varmuza S, Tilly JL, Casper RF. Expression of apoptosis-related genes during human preimplantation embryo development: potential roles for the Harakiri gene product and Caspase-3 in blastomere fragmentation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:133–41. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag016.

- Scott L, Alvero R, Leondires M, Miller B. The morphology of human pronuclear embryos is positively related to blastocyst development and implantation. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:2394–403. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.11.2394.

- Tesarik J, Junca AM, Hazout A, Aubriot FX, Nathan C, Cohen-Bacrie P, Dumont-Hassan M. Embryos with high implantation potential after intracytoplasmic sperm injection can be recognized by a simple, non-invasive examination of pronuclear morphology. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1396–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.6.1396.

- Hnida C, Engenheiro E, Ziebe S. Computer-controlled, multilevel, morphometric analysis of blastomere size as biomarker of fragmentation and multinuclearity in human embryos. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:288–93. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh070.

- Moriwaki T, Suganuma N, Hayakawa M, Hibi H, Katsumata Y, Oguchi H, Furuhashi M. Embryo evaluation by analysing blastomere nuclei. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:152–6.

- Lundin K, Bergh C, Hardarson T. Early embryo cleavage is a strong indicator of embryo quality in human IVF. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2652–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.12.2652.

- Munne S, Alikani M, Tomkin G, Grifo J, Cohen J. Embryo morphology, developmental rates, and maternal age are correlated with chromosome abnormalities. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:382–91.

- erriou P, Sapin C, Giorgetti C, Hans E, Spach JL, Roulier R. Embryo score is a better predictor of pregnancy than the number of transferred embryos or female age. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:525–31.

- Gregg, A.R., Skotko, B.G., Benkendorf, J.L., Monaghan, K.G., Bajaj, K., Best, R.G. et al, Noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, 2016 update: a position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2016;18:1056–1065.|

- R.J., Martin, C.L., Levy, B., Ballif, B.C., Eng, C.M. et al, Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2175–2184.

- Van den Veyver, I.B., Patel, A., Shaw, C.A., Pursley, A.N., Kang, S.H., Simovich, M.J. et al, Clinical use of array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) for prenatal diagnosis in 300 cases. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29:29–39.

- Devroey P, Pados G 1998 Preparation of endometrium for egg donation. Human Reproduction Update 4, 856–861.

- Cecilia T. Valdes, Carlos Simon, Carlos SimonAmy Schutt: Implantation failure of endometrial origin: it is not pathology, but our failure to synchronize the developing embryo with a receptive endometrium. Fertil Steril 2017;108, 1:1518

- Diaz-Gimeno P, Ruiz-Alonso M, Blesa D, Bosch N, Martinez-Conejero JA, Alama P, et al. The accuracy and reproducibility of the endometrial receptivity array is superior to histology as a diagnostic method for endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:508–517.

- Dunn CL, Kelly RW, Critchley HO. Deciduali-zation of the human endometrial stromal cell: an enigmatic transformation. Reprod Biomed Online. 2003;7(2):151–61.

- Critchley HO, Jones RL, Lea RG, Drudy TA, Kelly RW, Williams AR, Baird DT. Role of inflammatory mediators in human endometrium during progesterone withdrawal and early pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999a;84:240–248.

- Antinidatory effect of luteal phase administration of mifepristone (RU486) is associated with changes in endometrial prostaglandins during the implantation window. Nayak NR, Sengupta J, Ghosh D.Contraception. 1998 Aug; 58(2):111-7.

- Achache H, Tsafrir A, Prus D, Reich R, Revel A. Defective endometrial prostaglandin synthesis identified in patients with repeated implantation failure undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(4):1271–8.

- Kennedy TG, Gillio-Meina C, Phang SH. Prostaglandins and the initiation of blastocyst implantation and decidualization. Reproduction. 2007;134(5):635–43.

- Richards RG, Brar AK, Frank GR, Hartman SM, Jikihara H. Fibroblast cells from term human decidua closely resemble endometrial stromal cells: induction of prolactin and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 expression. Biol Reprod. 1995;52(3):609–15.

- Sugino N, Kashida S, Karube-Harada A, Takiguchi S, Kato H. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle and in early pregnancy. Reproduction. 2002;123(3):379–87.

- Simón, C., Martın, J.C., Pellicer, A. Paracrine regulators of implantation. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;14:815–826.

- Tuckerman E, Mariee N, Prakash A, Li TC, Laird S. Uterine natural killer cells in peri-implantation endometrium from women with repeated implant-ation failure after IVF. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;87(1-2):60–66.

- Sugino N, Kashida S, Karube-Harada A, Takiguchi S, Kato H. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle and in early pregnancy. Reproduction. 2002;123(3):379–87.

- Abberton KM, Taylor NH, Healy DL, Rogers PA. Vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in arterioles of the human endometrium. Hum Reprod 1999b;14:1072–1079. [PubMed]

- Telgmann R, Gellersen B. Marker genes of decidualization: activation of the decidual prolactin gene.Hum Reprod Update. 1998 Sep-Oct;4(5):472-9.

- Analysis on the promoter region of human decidual prolactin gene in the progesterone-induced decidualization and cAMP-induced decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. Wang DF, Minoura H, Sugiyama T, Tanaka K, Kawato H, Toyoda N, Sagawa N.Mol Cell Biochem. 2007 Jun; 300(1-2):239-47. Epub 2006 Dec 23.

- Marker genes of decidualization: activation of the decidual prolactin gene. Telgmann R, Gellersen B.Hum Reprod Update. 1998 Sep-Oct; 4(5):472-9.

- Brosens JJ, Hayashi N, White JO. Progesterone receptor regulates decidual prolactin expression in differentiating human endometrial stromal cells. Endocrinology 1999;140:4809–4820.

- Fan X, Krieg S, Kuo CJ, Wiegand SJ, Rabinovitch M, Druzin ML, Brenner RM, Giudice LC, Nayak NR. VEGF blockade inhibits angiogenesis and reepithelialization of endometrium. FASEB J2008;22:3571–3580.

- Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and funcGuo Y, He B, Xu X, Wang J. Comprehensive analysis of leukocytes, vascularization and matrix metalloproteinases in human menstrual xenograft model. PLoS One 2011;6:e16840. tions. Immunity 2010;32:593–604.

- Hannan NJ, Salamonsen LA. Role of chemokines in the endometrium and in embryo implantation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2007;19:266–272.

- Henderson TA, Saunders PT, Moffett-King A, Groome NP, Critchley HO. Steroid receptor expression in uterine natural killer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:440–449.

- Kelly RW, King AE, Critchley HO. Cytokine control in human endometrium. Reproduction2001;121:3–19.

- Koopman LA, Kopcow HD, Rybalov B, Boyson JE, Orange JS, Schatz F, Masch R, Lockwood CJ, Schachter AD, Park PJ et al. Human decidual natural killer cells are a unique NK cell subset with immunomodulatory potential. J Exp Med 2003;198:1201–1212.

- Malik S, Day K, Perrault I, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith SK. Reduced levels of VEGF-A and MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity and increased TNF-alpha in menstrual endometrium and effluent in women with menorrhagia. Hum Reprod 2006;21:2158–2166.

- Maybin JA, Hirani N, Brown P, Jabbour HN, Critchley HO. The regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by hypoxia and prostaglandin F2{alpha} during human endometrial repair. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011b;96:2475–2483.

- Mints M, Hultenby K, Zetterberg E, Blomgren B, Falconer C, Rogers R, Palmblad J. Wall discontinuities and increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor-A and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in endometrial blood vessels of women with menorrhagia. Fertil Steril 2007;88:691–697.

- Moffett-King A. Natural killer cells and pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 2002;2:656–663.

- Sharkey AM, Day K, McPherson A, Malik S, Licence D, Smith SK, Charnock-Jones DS. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human endometrium is regulated by hypoxia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:402–409.

- Dimitriadis E, White CA, Jones RL, Salamonsen LA. Cytokines, chemokines and growth factors in endometrium related to implantation. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:613–630.

- Cytokines in implantation. Salamonsen LA, Dimitriadis E, Robb L.Semin Reprod Med. 2000; 18(3):299-310.

- Review: LIF and IL11 in trophoblast-endometrial interactions during the establishment of pregnancy.

- Dimitriadis E, Menkhorst E, Salamonsen LA, Paiva P.Placenta. 2010 Mar; 31 Suppl:S99-104. Epub 2010 Feb 2.

- Herbst RS, Review of epidermal growth factor receptor biology, in International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, vol. 59, 2 Suppl, 2004, pp. 21–6

- AM Petit, J Rak, MC Hung, P Rockwell, N Goldstein, B Fendly and RS Kerbel, Neutralizing antibodies against epidermal growth factor and ErbB-2/neu receptor tyrosine kinases down-regulate vascular endothelial growth factor production by tumor cells in vitro and in vivo: angiogenic implications for signal transduction therapy of solid tumors, in American Journal of Pathology, vol. 151, nº 6, dicembre 1997, pp. 1523-30, PMID 9403702.

- V Lindner, M A Reidy, Proliferation of smooth muscle cells after vascular injury is inhibited by an antibody against basic fibroblast growth factor (PDF), in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A., vol. 88, nº 9, 1º maggio 1991, pp. 3739-43, PMID 2023924.

- Marie C. Prewett, Andrea T. Hooper, Rajiv Bassi, Lee M. Ellis, Harlan W. Waksal and Daniel J. Hicklin, Enhanced Antitumor Activity of Anti-epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody IMC-C225 in Combination with Irinotecan (CPT-11) against Human Colorectal Tumor Xenografts (PDF), in American Association for Cancer Research, vol. 8, nº 5, maggio 2002, pp. 994-1003,

- J. Baselga, D. Pfister, M. R. Cooper, R. Cohen, B. Burtness, M. Bos, G. D’Andrea, A. Seidman, L. Norton, K. Gunnett, J. Falcey, V. Anderson, H. Waksal, J. Mendelsohn, Phase I Studies of Anti–Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Chimeric Antibody C225 Alone and in Combination With Cisplatin, in Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 18, nº 4, febbraio 2000, pp. 904-14

- Lockwood CJ, Krikun G, Runic R, Schwartz LB, Mesia AF, Schatz F. Progestin-epidermal growth factor regulation of tissue factor expression during decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000 Jan;85(1):297-301.

- Lockwood CJ, Krikun G, Schatz F. Decidual cell-expressed tissue factor maintains hemostasis in human endometrium. nn N Y Acad Sci. 2001 Sep;943:77-88.

- Progestin-epidermal growth factor regulation of tissue factor expression during decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells.

- Lockwood CJ, Krikun G, Runic R, Schwartz LB, Mesia AF, Schatz F.J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000 Jan; 85(1):297-301.

- Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ (November 2007). “p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF”. Nature. 450 (7170): 721–724

- Aghajanova L (December 2004). “Leukemia inhibitory factor and human embryo implantation”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1034: 176–83.

- Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Köntgen F, Abbondanzo SJ (September 1992). “Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor”. Nature. 359 (6390): 76–9.

- Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Kontgen F, Abbondanzo SJ. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukemia inhibitory factor. Nature. 1992;359:76–79. doi: 10.1038/359076a0

- Robb L, Li R, Hartley L, Nandurkar HH, Koentgen F, Begley CG. Infertility in female mice lacking the receptor for interleukin 11 is due to a defective uterine response to implantation. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:303–308.

- Du XX, Williams DA. Interleukin-11: Review of molecular, cell biology and clinical use. Blood 1997;89:3897–3908.

- Cork BA, Li TC, Warren MA, Laird SM. Interleukin-11 (IL-11) in human endometrium: expression throughout the menstrual cycle and the effects of cytokines on endometrial IL-11 production in vitro. J Reprod Immunol. 2001;50:3–17. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0378(00)00089-9.

- Chen HF, Lin CY, Chao KH, Wu MY, Yang YS, Ho HN. Defective production of interleukin-11 by decidua and chorionic villi in human anembryonic pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2320–2328.

- Cork BA, Tuckerman EM, Li TC, Laird SM. Expression of interleukin (IL)-11 receptor by the human endometrium in vivo and effects of IL-11, IL-6 and LIF on the production of MMP and cytokines by human endometrial cells in vitro. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:841–848. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.9.841.

- Dimitriadis E, Robb L, Salamonsen LA. Interleukin 11 advances progesterone-induced decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:636–643. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.7.636.

- Dimitriadis E, Robb L, Salamonsen LA. Interleukin 11 advances progesterone-induced decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:636–643.

- Tanaka T, Sakamoto T, Miyama M, Ogita S, Umesaki N. Interleukin-11 enhances cell survival of decidualized normal human endometrial stromal cells. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2001;15:272–278.

- Karpovich N, Chobotova K, Carver J, Heath JK, Barlow DH, Mardon HJ. Expression and function of interleukin-11 and its receptor alpha in the human endometrium. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:75–80. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag012.

- Bilinski P, Roopenian D, Gossler A. Maternal IL-11Rα function is required for normal decidua and fetoplacental development in mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2234–2243.

- Chen HF, Lin CY, Chao KH, Wu MY, Yang YS, Ho HN. Defective production of interleukin-11 by decidua and chorionic villi in human anembryonic pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2320–2328.

- Cork BA, Li TC, Warren MA, Laird SM. Interleukin-11 (IL-11) in human endometrium: expression throughout the menstrual cycle and the effects of cytokines on endometrial IL-11 production in vitro. J Reprod Immunol. 2001;50:3–17.

- Dimitriadis E, Salamonsen LA, Robb L. Expression of interleukin-11 during the human menstrual cycle: coincidence with stromal cell decidualization and relationship to leukaemia inhibitory factor and prolactin. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:907–914.

- Salamonsen LA, Dimitriadis E, Robb L. Cytokines in implanatation. Semin Reprod Med. 2000;18:299–310.

- Tanaka T, Sakamoto T, Miyama M, Ogita S, Umesaki N. Interleukin-11 enhances cell survival of decidualized normal human endometrial stromal cells. Gynaecol Endocrinol. 2001;15:272–278.

- Graham JD, Clarke CL. Physiological action of progesterone in target tissues. Endocr Rev1997;18:502–519

- Lessey BA, Killam AP, Metzger DA, Haney AF, Greene GL, McCarty KS Jr. Immunohistochemical analysis of human uterine estrogen and progesterone receptors throughout the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988;67:334–340

- Mote PA, Johnston JF, Manninen T, Tuohimaa P, Clarke CL. Detection of progesterone receptor forms A and B by immunohistochemical analysis. J Clin Pathol 2001;54:624–630.

- Zeyneloglu, H.B., Arici, A., Olive, D.L. Adverse effects of hydrosalpinx on pregnancy rates after in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:492–499.

- Meyer, W., Castelbaum, A., Somkuti, S., Sagoskin, A., Doyle, M., Harris, J. et al, Hydrosalpinges adversely affect markers of endometrial receptivity. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1393–1398.

- Penzias, A.S. Recurrent IVF failure: other factors. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1033–1038.

- Johnston-MacAnanny EB, Hartnett J, Engmann LL, Nulsen JC, Sanders MM, Benadiva CA. Chronic endometritis is a frequent finding in women with recurrent implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(2):437–41

- Inmaculada Moreno, Francisco M. Codoñer, Felipe Vilella, Diana Valbuena, Juan F. Martinez-Blanch, Jorge Jimenez-Almazán, Roberto Alonso, Pilar Alamá, Jose Remohí, Antonio Pellicer, Daniel Ramon, Carlos Simon. Evidence that the endometrial microbiota has an effect on implantation success or failure. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2016; 215 (6): 684

- Boivin, J., Griffiths, E., Venetis, C.A. Emotional distress in infertile women and failure of assisted reproductive technologies: meta-analysis of prospective psychosocial studies. Br Med J. 2011;342:d223.

- Broughton, D.E., Moley, K.H. Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity’s impact. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:840–847.

- Shapiro, B., Daneshmand, S., Garner, F., Aguirre, M., Hudson, C. Factors related to embryo-endometrium asynchrony in fresh IVF cycles increase in prevalence with maternal age. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:S287

- Díaz-Gimeno, P., Ruiz-Alonso, M., Blesa, D., Bosch, N., Martínez-Conejero, J.A., Alamá, P. et al, The accuracy and reproducibility of the endometrial receptivity array is superior to histology as a diagnostic method for endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:508–517.

- Garrido-Gomez T, Ruiz-Alonso M, Blesa D, Diaz-Gimeno P, Vilella F, Simon C. Profiling the gene signature of endometrial receptivity: clinical results. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1078–85.

- Giancotti FG, et al. (1999) Integrin signaling. Science. 285(5430): 1028-32.

- Schlaepfer DD, et al. (1994) Integrin-mediated signal transduction linked to Ras pathway by GRB2 binding to focal adhesion kinase. Nature. 372(6508): 786-91.

- Schlaepfer DD, et al. (1994) Integrin-mediated signal transduction linked to Ras pathway by GRB2 binding to focal adhesion kinase. Nature. 372(6508): 786-91.

- Schlaepfer DD, et al. (1998) Integrin signalling and tyrosine phosphorylation: just the FAKs? Trends Cell Biol. 8(4): 151-7.

- Di Carlo A. The role of matrix-metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and matrix-metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in angiogenesis. The inducer and inhibitor role of gelatinase A (MMP-2) and gelatinase B (MMP-9) in the formation of new blood vessels. Prevent Res, published on line 18. Oct. 2012, P&R Public. 34.

- Nagase H., Woessner J.F.Jr. “Matrix metalloproteinases”. The Journal of biological chemistry, 274 (31), 21491-21494, 1999.

- Schlaepfer DD, et al. (1998) Integrin signalling and tyrosine phosphorylation: just the FAKs? Trends Cell Biol. 8(4): 151-7.

- Schlaepfer DD, et al. (1994) Integrin-mediated signal transduction linked to Ras pathway by GRB2 binding to focal adhesion kinase. Nature. 372(6508): 786-91.

- Schlaepfer DD, et al. (1998) Integrin signalling and tyrosine phosphorylation: just the FAKs? Trends Cell Biol. 8(4): 151-7.

- Nagase H., Woessner J.F.Jr. “Matrix metalloproteinases”. The Journal of biological chemistry, 274 (31), 21491-21494, 1999.

- Sternlicht M.D., Werb Z. “How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior”. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 17, 463-516, 2001.

- Gellersen B1, Brosens IA, Brosens JJ.: Decidualization of the human endometrium: mechanisms, functions, and clinical perspectives. Semin Reprod Med. 2007 Nov;25(6):445-53.

- Dunn CL1, Kelly RW, Critchley HO.Decidualization of the human endometrial stromal cell: an enigmatic transformation. Reprod Biomed Online. 2003 Sep;7(2):151-61.

- Tang B, Guller S, Gurpide EEndocrine. 1997 Jun; 6(3):301-7.Mechanisms involved in the decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. .Acta Eur Fertil. 1993 Sep-Oct; 24(5):221-3.

- Baniţă IM1, Bogdan F.: “Study of chorial villi formation and evolution”. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 1998 Jan-Dec;44(1-4):11-6.

- Castellucci M, Kosanke G, Verdenelli F, Huppertz B, Kaufmann P.: “Villous sprouting: fundamental mechanisms of human placental development”. Hum Reprod Update. 2000 Sep-Oct; 6(5):485-94.

- Castellucci M, Scheper M, Scheffen I, Celona A, Kaufmann P.: The development of the human placental villous tree. Anat Embryol (Berl). 1990; 181(2):117-28.

- Frank H. Netter, Atlante di anatomia umana, terza edizione, Elsevier Masson, 2007. ISBN 978-88-214-2976-7

- Anastasi G. e altri, “Trattato di anatomia umana” Edi Ermes 2006

- Testut L. et Latarjet A.: “Traitè d’anatomie humaine”. G. Doin & CIE Editeurs;1949.

- Rao CV 2001 Multiple novel roles of luteinizing hormone. Fertility and Sterility 76, 1097–1100.

- Shemesh M 2001 Actions of gonadotrophins on the uterus. Reproduction 121, 835–842.

- Srisuparp S, Strakova Z, Fazleabas AT 2001 The role of chorionic gonadotropin (CG) in blastocyst implantation. Archives of Medical Research 32, 627–634

- Stepien A, Shemesh M, Ziecik AJ 1999 Luteinizing hormone receptor kinetic and LH-induced prostaglandin production throughout the oestrous cycle in porcine endometrium. Reproduction Nutrition et Développement 39, 663–674.

- Bourgain C, Smitz J, Camus M et al. 1994 Human endometrial maturation is markedly improved after luteal supplementation of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue/human menopausal gonadotrophin stimulated cycles. Human Reproduction 9, 32–40

- Richard A. Jungmann and John S. Schweppe: “Mechanism of Action of Gonadotropin”. J. Biol. Chem. 1972, 247:5535-5542.

- Levy DP, Navarro JM, Schattman GL, Davis OK, Rosenwaks Z (2000) The role of LH in ovarian stimulation: exogenous LH, let’s design the future. Hum Reprod; 15:2258-2265.

- De Placido G, Alviggi C, Mollo A, Strina I, Ranieri A, Alviggi E, Wilding M, Varricchio MT, Borrelli AL and Conforti S (2004) Effects of recombinant LH (rLH) supplementation during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) in normogonadotrophic women with an initial inadequate response to recombinant FSH (rFSH) after pituitary downregulation. Clin Endocrinol; 60:637-643.

- De Placido G, Alviggi C, Perino A, Strina I, Lisi F, Fasolino A, De Palo R, Ranieri A, Colacurci N and Mollo A on behalf of the Italian Collaborative Group on Recombinant Human Luteinizing Hormon. (2005) Recombinant human LH supplementation versus recombinant human FSH (rFSH) step-up protocol during controlled ovarian stimulation in normogonadotrophic women with initial inadequate ovarian response to rFSH. A multicentre, prospective, randomized controlled trial. Human Reproduction; 20(2):390-396.

- Chappel SC and Howles C (1991) Revaluation of the roles of luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone in the ovulatory process. Hum Reprod; 6:1206-12.

- Direito A., Bailly, S., Mariani, A., Ecochard, R. Relationships between the luteinizing hormone surge and other characteristics of the menstrual cycle in normally ovulating women. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:279–285.e3.Abstract| Full Text| Full Text PDF

- Juan-Enrique Schwarze, et al: Addition of neither recombinant nor urinary luteinizing hormone was associated with an improvement in the outcome of autologous in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmatic sperm injection cycles under regular clinical settings: a multicenter observational analysis. Fertil Steril 2016;106,7:1714-1717e1

- Irani M, Robles A, Gunnala V, Reichman DE, Rosenwarks: Optimal parameters for determining the LH surge in natural cycle frozen-thawed embryo transfers. Fertil Steril 2016;106,3S:e143

- Bourgain C, Ubaldi F, Tavaniotou A et al. 2002 Endometrial hormone receptors and proliferation index in the periovulatory phase of stimulated embryo transfer cycles in comparison with natural cycles and relation to clinical pregnancy outcome. Fertility and Sterility 78, 237–244

- Devroey P, Pados G 1998 Preparation of endometrium for egg donation. Human Reproduction Update 4, 856–861.

- Domínguez F, Remohí J, Pellicer A, Simón C 2003 Human endometrial receptivity: a genomic approach. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 6, 332–338.

- Bhagwat SR, Chandrashekar DS, Kakar R, Davuluri S, Bajpai AK, Nayak S, et al. Endometrial receptivity: a revisit to functional genomics studies on human endometrium and creation of HGEx-Erdb. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58419. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Gimeno P, Ruiz-Alonso M, Blesa D, Bosch N, Martinez-Conejero JA, Alama P, et al. The accuracy and reproducibility of the endometrial receptivity array is superior to histology as a diag-nostic method for endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(2):508–17. [PubMed]

- Revel A, Achache H, Stevens J, Smith Y, Reich R. MicroRNAs are associated with human embryo implantation defects. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(10):2830–40.

- Koler, M., Achache, H., Tsafrir, A., Smith, Y., Revel, A., Reich, R. Disrupted gene pattern in patients with repeated in vitro fertilization (IVF) failure. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2541–2548.

- Koot, Y.E., Van Hooff, S.R., Boomsma, C.M., Van Leenen, D., Koerkamp, M.J.G., Goddijn, M. et al, An endometrial gene expression signature accurately predicts recurrent implantation failure after IVF.Sci Rep. 2016;6:19411.

- Bersinger, N.A., Wunder, D.M., Birkhäuser, M.H., Mueller, M.D. Gene expression in cultured endometrium from women with different outcomes following IVF. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14:475–484.

- Simon, C., Vladimirov, I.K., Castillon Cortes, G., Ortega, I., Cabanillas, S., Vidal, C. et al, Prospective, randomized study of the endometrial receptivity analysis (ERA) test in the infertility work-up to guide personalized embryo transfer versus fresh transfer or deferred embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:e46–e47.Abstract | Full Text | Full Text PDF

- Díaz-Gimeno, P., Horcajadas, J.A., Martínez-Conejero, J.A., Esteban, F.J., Alamá, P., Pellicer, A. et al, A gomic diagnostic tool for human endometrial receptivity based on the transcriptomic signature. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:50–60.ene15.Abstract| Full Text| Full Text PDF

- Ponnampalam, A.P., Weston, G.C., Trajstman, A.C., Susil, B., Rogers, P.A. Molecular classification of human endometrial cycle stages by transcriptional profiling. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:879–893.

- Talbi, S., Hamilton, A., Vo, K., Tulac, S., Overgaard, M.T., Dosiou, C. et al, Molecular phenotyping of human endometrium distinguishes menstrual cycle phases and underlying biological processes in normo-ovulatory women. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1097–1121.

- Diaz-Gimeno P, Horcajadas JA, Martinez-Conejero JA, Esteban FJ, Alama P, Pellicer A, et al. A genomic diagnostic tool for human endometrial receptivity based on the transcriptomic signature. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(1):50–60. [PubMed]

- Riesewijk, A., Martín, J., van Os, R., Horcajadas, J.A., Polman, J., Pellicer, A. et al, Gene expression profiling of human endometrial receptivity on days LH+ 2 versus LH+ 7 by microarray technology.Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:253–264.

- Ruiz-Alonso, M., Blesa, D., Simón, C. The genomics of the human endometrium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:1931–1942.

- Magli, M., Gianaroli, L., Ferraretti, A., Fortini, D., Aicardi, G., Montanaro, N. Rescue of implantation potential in embryos with poor prognosis by assisted zona hatching. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1331–1335.

- Pehlivan, T., Rubio, C., Rodrigo, L., Romero, J., Remohi, J., Simon, C. et al, Impact of preimplantation genetic diagnosis on IVF outcome in implantation failure patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2003;6:232–237.

- Blockeel, C., Schutyser, V., De Vos, A., Verpoest, W., De Vos, M., Staessen, C. et al, Prospectively randomized controlled trial of PGS in IVF/ICSI patients with poor implantation. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;17:848–854.

- Gargett CE, Schwab KE, Zillwood RM, Nguyen HP, Wu D. Isolation and culture of epithelial progenitors and mesenchymal stem cells from human endometrium. Biol Reprod 2009;80:1136–1145.

- Cervello I, Mas A, Gil-Sanchis C, Simon C. Somatic stem cells in the human endometrium. Semin Reprod Med 2013;31:69–76.

- Co-expression of two perivascular cell markers isolates mesenchymal stem-like cells from human endometrium. Schwab KE, Gargett CE um Reprod. 2007 Nov; 22(11):2903-11.

- Gargett CE. Uterine stem cells: what is the evidence? Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(1):87–101.

- Cervello I, Simon C. Somatic stem cells in the endo-metrium. Reprod Sci. 2009;16(2):200–5.

- Dimitrov R, Kyurkchiev D, Timeva T, Yunakova M, Stamenova M, Shterev A, et al. First-trimester human decidua contains a population of mesenchymal stem cells. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):210–9.

- Gargett CE, Schwab KE, Zillwood RM, Nguyen HP, Wu D. Isolation and culture of epithelial progenitors and mesenchymal stem cells from human endometrium. Biol Reprod. 2009;80(6):1136–45.[PMC free article] [PubMed

- Mints M, Jansson M, Sadeghi B, Westgren M, Uzunel M, Hassan M, et al. Endometrial endothelial cells are derived from donor stem cells in a bone marrow transplant recipient. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(1):139–43.

- Chan RW, Schwab KE, Gargett CE. Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70(6):1738–50.

- Meng X, Ichim TE, Zhong J, Rogers A, Yin Z, Jackson J, et al. Endometrial regenerative cells: a novel stem cell population. J Transl Med. 2007;15(5):57.

- Chan RW, Kaitu’u-Lino T, Gargett CE. Role of label-retaining cells in estrogen-induced endometrial regeneration. Reprod Sci. 2012;19(1):102–14.

- Gargett CE, Schwab KE, Brosens JJ, Puttemans P, Benagiano G, Brosens I. Potential role of endometrial stem/progenitor cells in the pathogenesis of early-onset endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod 2014;20:591–598.

- Makrigiannakis A. Repeated implantation failure: Immunological aspects and evidence based treatment modalities. In: Makrigiannakis A, editor. Proceeding of MSRM International Meeting “Implantation-recurrent miscarriages science and clinical aspects”; 2010 Sept 24-26; Chania, Crete, Greece: Mediterranean Society for Reproductive Medicine; 2010. pp. 21–2.

- Tuckerman E, Mariee N, Prakash A, Li TC, Laird S. Uterine natural killer cells in peri-implantation endometrium from women with repeated implant-ation failure after IVF. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;87(1-2):60–6.

- Flynn L, Byrne B, Carton J, Kelehan P, O’Herlihy C, O’Farrelly C. Menstrual cycle dependent fluctuations in NK and T-lymphocyte subsets from non-pregnant human endometrium. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2000;43(4):209–17.

- Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J. Dating the endometrial biopsy. Fertil Steril. 1950;1:3–25.

- Salker M, Teklenburg G, Molokhia M, Lavery S, Trew G, Aojanepong T, et al. Natural selection of human embryos: impaired decidualization of endometrium disables embryo-maternal interactions and causes recurrent pregnancy loss. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):10287

- Thornhill AR, deDie-Smulders CE, Geraedts JP, Harper JC, Harton GL, Lavery SA, et al. ESHRE PGD Consortium ‘Best practice guidelines for clinical preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and preimplantation genetic screening (PGS)’ Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):35–48.

- Stephenson MD, Fluker MR. Treatment of repeated unexplained in vitro fertilization failure with intravenous immunoglobulin: a randomized, placebo controlled Canadian trial. Fertil Steril. 2000;74(6):1108–13. [PubMed

- Tan BK, Vandekerckhove P, Kennedy R, Keay SD. Investigation and current management of recurrent IVF treatment failure in the UK. BJOG. 2005;112(6):773–80.

- Toth B, Wurfel W, Germeyer A, Hirv K, Makrigiannakis A, Strowitzki T. Disorders of implantation–are there diagnostic and therapeutic options? J Reprod Immunol. 2011;90(1):117–23.

- Coulam CB. Implantation failure and immunotherapy. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(6):1338–40.

- Balasch J, Creus M, Fabregues F, Font J, Martorell J, Vanrell JA. Intravenous immunoglobulin preceding in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer for patients with repeated failure of embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(3):655–8. [PubMed]

- Sher G, Zouves C, Feinman M, Maassarani G, Matzner W, Chong P, et al. A rational basis for the use of combined heparin/aspirin and IVIG immunotherapy in the treatment of recurrent IVF failure associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1998;39(6):391–4. [PubMed]

- Christiansen OB, Pedersen B, Rosgaard A, Husth M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial of intravenous immunoglobulin in the preven-tion of recurrent miscarriage: evidence for a thera-peutic effect in women with secondary recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(3):809–16.

- Coulam CB, Acacio B. Does immunotherapy for treatment of reproductive failure enhance live births? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67(4):296–304.

- Stephenson MD, Kutteh WH, Purkiss S, Librach C, Schultz P, Houlihan E, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin and idiopathic secondary recurrent miscarriage: a multicentered randomized placebo-controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(9):2203–9.

- Stephenson MD, Fluker MR. Treatment of repeated unexplained in vitro fertilization failure with intravenous immunoglobulin: a randomized, placebo controlled Canadian trial. Fertil Steril. 2000;74(6):1108–13.

- Barash A, Dekel N, Fieldust S, Segal I, Schechtman E, Granot I. Local injury to the endometrium doubles the incidence of successful pregnancies in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(6):1317–22.

- Narvekar SA, Gupta N, Shetty N, Kottur A, Srinivas M, Rao KA. Does local endometrial injury in the nontransfer cycle improve the IVF-ET outcome in the subsequent cycle in patients with previous unsuccessful IVF? A randomized con-trolled pilot study. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2010;3(1):15–9.[

-

Karimzadeh MA, Ayazi Rozbahani M, Tabibnejad N. Endometrial local injury improves the pregnancy rate among reccurent implantation failure patients undergoing in vitro fertilization/intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection: a randomised clinical trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;49(6):677–80.

- Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Aldo PB, Barash A, Or Y, Schechtman E, et al. Local injury of the endometrium induces an inflammatory response that promotes successful implantation. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2030–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Narvekar SA, Gupta N, Shetty N, Kottur A, Srinivas M, Rao KA. Does local endometrial injury in the nontransfer cycle improve the IVF-ET outcome in the subsequent cycle in patients with previous unsuccessful IVF? A randomized con-trolled pilot study. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2010;3(1):15–9

- Zhou L, Li R, Wang R, Huang HX, Zhong K. Local injury to the endometrium in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation cycles improves implant-ation rates. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(5):1166–76. [PubMed]

- Potdar N, Gelbaya T, Nardo LG. Endometrial in-jury to overcome recurrent embryo implantation failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25(6):561–71. [PubMed]

- Shohayeb A, El-Khayat W. Does a single endometrial biopsy regimen (SEBR) improve ICSI outcome in patients with repeated implantation failure? A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;164(2):176–9. [PubMed]

- Rubio C, Simon C, Mercader A, Garcia-Velasco J, Remohi J, Pellicer A. Clinical experience employing co-culture of human embryos with autologous human endometrial epithelial cells. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(Suppl 6):31–8. [PubMed]

- Puissant F, Van Rysselberge M, Barlow P, Deweze J, Leroy F. Embryo scoring as a prognostic tool in IVF treatment. Hum Reprod. 1987;2:705–8.

- Zhu J, Meniru GI, Craft IL. Embryo developmental stage at transfer influences outcome of treatment with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Assisted Reproduction Genetics. 1997;14:245–9.

- Hu Y, Maxson WS, Hoffman DI, Ory SJ, Eager S, Dupre J, Lu C. Maximizing pregnancy rates and limiting higher-order multiple conceptions by determining the optimal number of embryos to transfer based on quality. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:650–7. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00024-7. [PubMed][Cross Ref]

- Ebner T, Yaman C, Moser M, Sommergruber M, Polz W, Tews G. Embryo fragmentation in vitro and its impact on treatment and pregnancy outcome. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:281–5. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)01904-5. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Steer CV, Mills CL, Tan SL, Campbell S, Edwards RG. The cumulative embryo score: a predictive embryo scoring technique to select the optimal number of embryos to transfer in an in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer programme. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:117–9. [PubMed]

- Raziel A, Schachter M, Strassburger D, Bern O, Ron-El R, Friedler S. Favorable influence of local injury to the endometrium in intracytoplasmic sperm injection patients with high-order implantation failure. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(1):198–201. [PubMed]

- The effect of endometrial injury on ongoing pregnancy rate in unselected subfertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a randomized controlled trial. Yeung TW, Chai J, Li RH, Lee VC, Ho PC, Ng EH. Hum Reprod. 2014 Nov; 29(11):2474-81. Epub 2014 Sep 8.

-

Trninić-Pjević A, Kopitović V, Pop-Trajković S, Bjelica A, Bujas I, Tabs D, et al. Effect of hysteroscopic examination on the outcome of in vitro fertilization. Vojnosanit Pregl Mil-Med Pharm Rev. 2011;68(6):476–80. [PubMed]

- Karimzade MA, Oskouian H, Ahmadi S, Oskouian L. Local injury to the endometrium on the day of oocyte retrieval has a negative impact on implantation in assisted reproductive cycles: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(3):499–503. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1166-1.

- Shufaro Y, Simon A, Laufer N, Fatum M. Thin unresponsive endometrium–a possible complication of surgical curettage compromising ART outcome. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008;25(8):421–425. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9245-y.

1 commento

Hey! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this website?

I’m getting tired of Wordpress because I’ve had issues

with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform.

I would be fantastic if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.