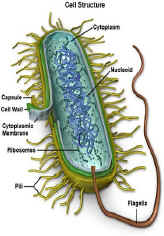

Vaginite da mycoplasmi: malattia sessualmente trasmessa causata da micolplasmi. I Mycoplasmi sono batteri gram+ aerobi obbligati o aerobi/anaerobi facoltativi. Sono i più piccoli procarioti in grado di moltiplicarsi in modo autonomo, caratterizzati da  assenza di parete batterica, sostituita da una membrana flessibile, con conseguente pleiomorfismo che ne rende difficile l’identificazione anche dopo cultura in vitro. Alcune specie di micoplasma hanno anche l’unica capacità di sfuggire completamente agli attacchi del sistema immunitario. Una volta adesi alle cellule epiteliali, il loro plasma e lo strato proteinico possono apparire come la parete della cellula ospite e quindi il sistema immunitario non riesce a riconoscerli come agenti esterni all’organismo.

assenza di parete batterica, sostituita da una membrana flessibile, con conseguente pleiomorfismo che ne rende difficile l’identificazione anche dopo cultura in vitro. Alcune specie di micoplasma hanno anche l’unica capacità di sfuggire completamente agli attacchi del sistema immunitario. Una volta adesi alle cellule epiteliali, il loro plasma e lo strato proteinico possono apparire come la parete della cellula ospite e quindi il sistema immunitario non riesce a riconoscerli come agenti esterni all’organismo.

Sono state isolate circa 40 specie di Mycoplasmi: quelli che rivestono maggiore importanza per la loro frequenza nella patologia ostetrico-ginecologica sono il Mycoplasma hominis e l’Ureaplasma urealyticum. Quest’ultimo, da solo o in associazione con il M. hominis, è responsabile del 30% circa delle infezioni cervico-vaginali, vulviti e uretriti rivestendo un ruolo di patogeno “emergente” sia in ostetricia che in ginecologia .

La loro azione patogena si esplica mediante una prima fase di “adesività”, in modo particolare alla parete delle mucose, seguita dalla liberazione di sostanze tossiche quali perossidi e ammoniaca (da cui il nome urealyticum) o enzimi in grado di danneggiare la superficie cellulare epiteliale.

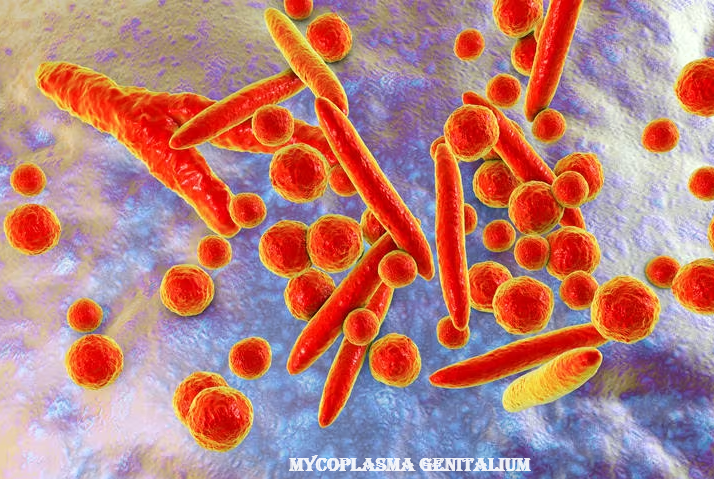

Di recente, soprattutto in casi di infezioni a decorso cronico, è stata focalizzata l’attenzione su un’altra specie, M. genitalium, a trasmissione prevalentemente sessuale. La sua azione patogena è legata non solo alla capacità adesiva ma alla capacità di penetrare nelle cellule della mucosa genito-urinaria.

Tuttavia spesso questi microrganismi coesistono con il loro ospite in un equilibrio senza sintomatologia clinica che può rompersi, esitando in malattia conclamata con tendenza alla cronicizzazione.

Sintomatologia:

- L’infezione cronicizzata può essere esente da sintomatologia.

- La sintomatologia classica prevede leucorrea muco-purulenta grigio-giallastra e prurito vulvo-vaginale,

- disuria, ematuria e pollachiuria.

- Dispareunia

Diagnosi:

- All’osservazione vaginale con speculum si nota la mucosa vaginale e cervicale arrossata e ricoperta da secrezioni adese e maleodoranti.

- Cultura in vitro su appositi terreni di cultura del secreto vaginale raccolto nel fornice posteriore mediante tampone. Il terreno di trasporto deve essere uguale a quello di cultura. Ma la percentuale di falsi negativi è piuttosto frequente ed in caso di positività occorre tener presente che il mycoplasma può essere presente per molto tempo dopo I’infezione. Per tali motivi.la maggior parte delle diagnosi è di tipo sierologico.

- Tests sierologici: Il test sierologico più comunemente disponibile è quello della fissazione del complemento (CF), sebbene un crescente numero di laboratori di diagnosi stia utilizzando il test enzimatico (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA). Con entrambi i metodi circa il 90% dei pazienti dimostra un’elevazione di quattro volte nei titoli (dopo 2-3 settimane) o un titofo singolo di 1:32 o più. Questi test comportano, comunque, dei problemi: primo, il titolo CF può rimanere elevato per un anno dopo l’infezione; secondo, I’antigene glicolipidico usato per il test non è specifico per il Mycoplasma; possono esservi quindi dei falsi positivi, ad esempio in alcune sindromi neurologiche e nelle pancreatiti; terzo, esistono reazioni falsamente negative con entrambi i test; quarto, alcuni adulti producono solo anticorpi IgG, così la fissazione del complemento, che determina principalmente IgM, con più facilità è falsamente negativa; quinto, gli anticorpi compaiono solo dopo 7-10 giorni dall’inizio della malattia, non producendo quindi nessun aiuto diagnostico precoce della causa d’infezione; in ultimo, il rilievo delle IgM non prova che l’infezione sia in atto, poiché esse possono persistere per mesi, potendo indicare quindi un’infezione recente, piuttosto che presente al momento.

- Metodi di determinazione diretta includono tecniche di ricerca antigenica, sonde a DNA e PCR. Di queste, la più promettente in termini di velocità, sensibilità e specificità è la PCR, sebbene costi e limitata disponibilità generale ne limitino l’uso routinario. Inoltre, la rilevanza della determinazione del Mycoplasma nelle secrezioni è limitata in vista di uno stato di portatore prolungato.

- PCR, Pro-calcitonina, leucocitosi neutrofila.

Praticamente per la diagnosi vengono valutati uno dei seguenti parametri:

a) rialzo di quattro volte del titolo anticorpale,

b) titolo singolo anticorpale > l:32,

c) titolo d’agglutinine fredde >1:64

d) singola determinazione delle IgM.

Complicazioni: In ostetricia molte osservazioni suggeriscono un ruolo importante nella patogenesi dell’aborto spontaneo e della rottura prematura delle membrane (PROM) e del parto pretermine, a causa di corionamnioniti e flogosi placentare; si osserva inoltre aumentata incidenza di polmoniti e meningiti neonatali (1-8).

In ginecologia è stato dimostrato come l’aumento della frequenza della eziologia infettiva sia causa di sterilità e di infertilità in circa il 30% di casi. Ciò può avvenire attraverso tre meccanismi:

- ostacolo alla migrazione degli spermatozoi, o per un aumento della viscosità del muco o per la riduzione del pH;

- mediante un effetto diretto dei germi sugli spermatozoi, in quanto il Mycoplasma attaccandosi ad essi forma una tumefazione del tratto intermedio;

- per un aumento degli anticorpi antispermatozoi (ASA).

COMPLICANZE: le vaginiti da micoplasma sono in grado di provocare (come conseguenza ultima) anche la Malattia Infiammatoria Pelvica (PID).

- ANTIBIOTICI – La terapia standard è rappresentata dalla tetraciclina cloridrato (Ambramicina® cps 250 mg x 2/die) o dall’eritromicina (Eritrocina® cpr 600 mg x 2/die) dose di 1 gr x 2/die) e fluorochinolonici (Ciproxin® cpr, Tavanic® cpr 250, 500 m, Levoxacin® cpr 250, 500 mg flacone ev 250 mg 50 ml). La doxiciclina (Bassado® cpr 100 mg x 2/die) ed i macrolidi (azitromicina -Azitrocin®, Zitromax® cpr- e claritromicina -Veclam® cpr- 500 mg x 2/die) possono sostituire, rispettivamente, la tetraciclina e I’eritromicina in caso di antibiotico-resistenza. Le tetracicline devono essere evitate nei bambini al di sotto degli 8 anni e nelle donne gravide. La durata della terapia è di 10-14 giorni ma terapie più lunghe possono evitare le recidive che si verificano nel 5-10% delle pazienti. Ricordare che la struttura del Mycoplasma, non essendo dotato di parete batterica, rimane del tutto immune nei confronti di quegli antibiotici che lavorano sulla sintesi della parete batterica stessa (penicilline e più in generale dei beta lattamici, come ad esempio Augmentin).

- Analgesici per alleviare il dolore, soprattutto nel caso di evoluzione verso una PID.

- Antipiretici nel caso di febbre.

- Gerbert S, Vial Y, Hohlfeld P. Witkin S: “Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in Second-Trimester Amniotic Fluid by Polymerase Chain Reaction Correlates with Subsequent Preterm Labor and Delivery”. J Infectious Diseases;2003;187,3:518-521

- Samantha J. Dando, Ilias Nitsos, Graeme R. Polglase, John P. Newnham, lan H. Jobe, and Christine L. Knox: “Ureaplasma parvum Undergoes Selection In Utero Resulting in Genetically Diverse Isolates Colonizing the Chorioamnion of Fetal Sheep”. Biol. Reprod. (2014) 90 (2): 27

- Gerber S, Vial Y, Hohlfeld P, Witkin SS. Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in second-trimester amniotic fluid by polymerase chain reaction correlates with subsequent preterm labor and delivery. J Infect Dis 2003; 187:518–521

- Perni SC, Vardhana S, Korneeva I, Tuttle SL, Paraskevas LR, Chasen ST, Kalish RB, Witkin SS. Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in midtrimester amniotic fluid: association with amniotic fluid cytokine levels and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 1382–1386.

- Yoon BH, Chang JW, Romero R. Isolation of Ureaplasma urealyticum from the amniotic cavity and adverse outcome in preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol 1998; 92:77–82.

- Knox CL, Cave DG, Farrell DJ, Eastment HT, Timms P. The role of Ureaplasma urealyticum in adverse pregnancy outcome. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1997; 37:45–51.

- Frew L, Stock SJ. Antimicrobial peptides and pregnancy. Reproduction 2011; 141:725–735.

- Cassell GH, Davis RO, Waites KB, Brown MB, Marriott PA, Stagno S, Davis JK. Isolation of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum from amniotic fluid at 16–20 weeks of gestation: potential effect on outcome of pregnancy. Sex Transm Dis 1983; 10:294–302.

- Ah-Kit X., Hoarau L., Graesslin O., Brun J. L. (2019). Follow-up and counselling after pelvic inflammatory disease: CNGOF and SPILF pelvic inflammatory diseases guidelines. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 47, 458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.gofs.2019.03.009, PMID: [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ajani T. A., Oluwasola T. A. O., Ajani Bakare R., A Ajani M., Department of Medical Microbiology, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria, Department of Histopathology, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria, Department of Medical Microbiology, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria (2017). The prevalence of, and risk factors for, Mycoplasma genitalium infection among infertile women in Ibadan: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 15, 613–618. d

- Aparicio D., Scheffer M. P., Marcos-Silva M., Vizarraga D., Sprankel L., Ratera M., et al.. (2020). Structure and mechanism of the nap adhesion complex from the human pathogen Mycoplasma genitalium. Nat. Commun. 11:2877.

- Aparicio D., Torres-Puig S., Ratera M., Querol E., Pinol J., Pich O. Q., et al.. (2018). Mycoplasma genitalium adhesin P110 binds sialic-acid human receptors. Nat. Commun. 9:4471.

- Ashshi A. M., Batwa S. A., Kutbi S. Y., Malibary F. A., Batwa M., Refaat B. (2015). Prevalence of 7 sexually transmitted organisms by multiplex real-time PCR in fallopian tube specimens collected from Saudi women with and without ectopic pregnancy. BMC Infect. Dis. 15:569.

- Averbach S. H., Hacker M. R., Yiu T., Modest A. M., Dimitrakoff J., Ricciotti H. A. (2013). Mycoplasma genitalium and preterm delivery at an urban community health center. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 123, 54–57.

- Baczynska A., Friis Svenstrup H., Fedder J., Birkelund S., Christiansen G. (2005). The use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of mycoplasma hominis antibodies in infertile women serum samples. Hum. Reprod. 20, 1277–1285.

- Baczynska A., Funch P., Fedder J., Knudsen H. J., Birkelund S., Christiansen G. (2007). Morphology of human fallopian tubes after infection with Mycoplasma genitalium and mycoplasma hominis–in vitro organ culture study. Hum. Reprod. 22, 968–979.

- Balkus J. E., Manhart L. E., Jensen J. S., Anzala O., Kimani J., Schwebke J., et al.. (2018). Mycoplasma genitalium infection in Kenyan and US women. Sex. Transm. Dis. 45, 514–521.

- Baumann L., Cina M., Egli-Gany D., Goutaki M., Halbeisen F. S., Lohrer G. R., et al.. (2018). Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in different population groups: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex. Transm. Infect. 94, 255–262.

- Bjartling C., Osser S., Persson K. (2010). The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG 117, 361–364.

- Bjartling C., Osser S., Persson K. (2012). Mycoplasma genitalium in cervicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease among women at a gynecologic outpatient service. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 206:476.e1.

- Borchsenius S. N., Daks A., Fedorova O., Chernova O., Barlev N. A. (2018). Effects of mycoplasma infection on the host organism response via p53/NF-kappaB signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 171–180.

- Brun J. L., Graesslin O., Fauconnier A., Verdon R., Agostini A., Bourret A., et al.. (2016). Updated French guidelines for diagnosis and management of pelvic inflammatory disease. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 134, 121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.11.028

- Carson S. A., Kallen A. N. (2021). Diagnosis and management of infertility: a review. JAMA 326, 65–76.

- Casillas-Vega N., Morfin-Otero R., Garcia S., Llaca-Diaz J., Rodriguez-Noriega E., Camacho-Ortiz A., et al.. (2016). Sexually transmitted pathogens, coinfections and risk factors in patients attending obstetrics and gynecology clinics in Jalisco, Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 58, 437–445.

- Clausen H. F., Fedder J., Drasbek M., Nielsen P. K., Toft B., Ingerslev H. J., et al.. (2001). Serological investigation of Mycoplasma genitalium in infertile women. Hum. Reprod. 16, 1866–1874.

- Cohen C. R., Mugo N. R., Astete S. G., Odondo R., Manhart L. E., Kiehlbauch J. A., et al.. (2005). Detection of Mycoplasma genitalium in women with laparoscopically diagnosed acute salpingitis. Sex. Transm. Infect. 81, 463–466.

- Contini C., Rotondo J. C., Magagnoli F., Maritati M., Seraceni S., Graziano A., et al.. (2018). Investigation on silent bacterial infections in specimens from pregnant women affected by spontaneous miscarriage. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 100–107.

- Cox C., Saxena N., Watt A. P., Gannon C., McKenna J. P., Fairley D. J., et al.. (2016). The common vaginal commensal bacterium Ureaplasma parvum is associated with chorioamnionitis in extreme preterm labor. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 29, 3646–3651.

- Damiao Gouveia A. C., Unemo M., Jensen J. S. (2018). In vitro activity of zoliflodacin (ETX0914) against macrolide-resistant, fluoroquinolone-resistant and antimicrobial-susceptible Mycoplasma genitalium strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1291–1294.

- Daubenspeck J. M., Totten A. H., Needham J., Feng M., Balish M. F., Atkinson T. P., et al.. (2020). Mycoplasma genitalium biofilms contain poly-GlcNAc and contribute to antibiotic resistance. Front. Microbiol. 11:585524.

- De Carvalho N. S., Palu G., Witkin S. S. (2020). Mycoplasma genitalium, a stealth female reproductive tract. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39, 229–234.

- de Jong A. S., Rahamat-Langendoen J. C., van Alphen P., Hilt N., van Herk C., Pont S., et al.. (2016). Large two-Centre study into the prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium and trichomonas vaginalis in the Netherlands. Int. J. STD AIDS 27, 856–860.

- Dehon P. M., McGowin C. L. (2017). The Immunopathogenesis of Mycoplasma genitalium infections in women: A narrative review. Sex. Transm. Dis. 44, 428–432.

- Desdorf R., Andersen N. M., Chen M. (2021). Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence and macrolide resistance-associated mutations and coinfection with chlamydia trachomatis in southern Jutland, Denmark. APMIS 129, 706–710.

- Doyle M., Vodstrcil L. A., Plummer E. L., Aguirre I., Fairley C. K., Bradshaw C. S. (2020). Nonquinolone options for the treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium in the era of increased resistance. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 7:ofaa291.

- Duan H., Qu L., Shou C. (2014a). Activation of EGFR-PI3K-AKT signaling is required for mycoplasma hyorhinis-promoted gastric cancer cell migration. Cancer Cell Int. 14:135.

- Duan H., Qu L., Shou C. (2014b). Mycoplasma hyorhinis induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer cell MGC803 via TLR4-NF-kappaB signaling. Cancer Lett. 354, 447–454.

- Dumke R. (2022). Molecular tools for typing Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Mycoplasma genitalium. Front. Microbiol. 13:904494.

- Durukan D., Doyle M., Murray G., Bodiyabadu K., Vodstrcil L., Chow E. P. F., et al.. (2020). Doxycycline and Sitafloxacin combination therapy for treating highly resistant Mycoplasma genitalium. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 1870–1874.

- Edwards R. K., Ferguson R. J., Reyes L., Brown M., Theriaque D. W., Duff P. (2006). Assessing the relationship between preterm delivery and various microorganisms recovered from the lower genital tract. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 19, 357–363.

- Fernandez-Huerta M., Barbera M. J., Serra-Pladevall J., Esperalba J., Martinez-Gomez X., Centeno C., et al.. (2020). Mycoplasma genitalium and antimicrobial resistance in Europe: a comprehensive review. Int. J. STD AIDS 31, 190–197.

- Fortner R. T., Terry K. L., Bender N., Brenner N., Hufnagel K., Butt J., et al.. (2019). Sexually transmitted infections and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: results from the Nurses’ health studies. Br. J. Cancer 120, 855–860.

- Fraser C. M., Gocayne J. D., White O., Adams M. D., Clayton R. A., Fleischmann R. D., et al.. (1995). The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science 270, 397–404.

- Gaydos C. A., Manhart L. E., Taylor S. N., Lillis R. A., Hook E. W., 3rd, Klausner J. D., et al.. (2019). Molecular testing for Mycoplasma genitalium in the United States: results from the AMES prospective multicenter clinical study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 57:e01125.

- Gedye C., Cardwell T., Dimopoulos N., Tan B. S., Jackson H., Svobodova S., et al.. (2016). Mycoplasma infection alters cancer stem cell properties in vitro. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 12, 156–161.

- Getman D., Jiang A., O’Donnell M., Cohen S. (2016). Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence, coinfection, and macrolide antibiotic resistance frequency in a multicenter clinical study cohort in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 2278–2283.

- Grzesko J., Elias M., Maczynska B., Kasprzykowska U., Tlaczala M., Goluda M. (2009). Occurrence of Mycoplasma genitalium in fertile and infertile women. Fertil. Steril. 91, 2376–2380.

- Haggerty C. L., Totten P. A., Astete S. G., Lee S., Hoferka S. L., Kelsey S. F., et al.. (2008). Failure of cefoxitin and doxycycline to eradicate endometrial Mycoplasma genitalium and the consequence for clinical cure of pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex. Transm. Infect. 84, 338–342.

- Haggerty C. L., Totten P. A., Astete S. G., Ness R. B. (2006). Mycoplasma genitalium among women with nongonococcal, nonchlamydial pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006:30184.

- Hakim M. S., Annisa L., Jariah R. O. A., Vink C. (2021). The mechanisms underlying antigenic variation and maintenance of genomic integrity in Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Mycoplasma genitalium. Arch. Microbiol. 203, 413–429.

- Harrison S. A., Olson K. M., Ratliff A. E., Xiao L., Van Der Pol B., Waites K. B., et al.. (2019). Mycoplasma genitalium coinfection in women with chlamydia trachomatis infection. Sex. Transm. Dis. 46, e101–e104.

- Hart T., Tang W. Y., Mansoor S. A. B., Chio M. T. W., Barkham T. (2020). Mycoplasma genitalium in Singapore is associated with chlamydia trachomatis infection and displays high macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance rates. BMC Infect. Dis. 20:314.

- Hitti J., Garcia P., Totten P., Paul K., Astete S., Holmes K. K. (2010). Correlates of cervical Mycoplasma genitalium and risk of preterm birth among Peruvian women. Sex. Transm. Dis. 37, 81–85.

- Hu P. C., Schaper U., Collier A. M., Clyde W. A., Jr., Horikawa M., Huang Y. S., et al.. (1987). A Mycoplasma genitalium protein resembling the mycoplasma pneumoniae attachment protein. Infect. Immun. 55, 1126–1131.

- Hussain S. P., Harris C. C. (2007). Inflammation and cancer: an ancient link with novel potentials. Int. J. Cancer 121, 2373–2380.

- Idahl A., Jurstrand M., Olofsson J. I., Fredlund H. (2015). Mycoplasma genitalium serum antibodies in infertile couples and fertile women. Sex. Transm. Infect. 91, 589–591. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052011 Idahl A., Le Cornet C., Gonzalez Maldonado S., Waterboer T., Bender N., Tjonneland A., et al.. (2020). Serologic markers of Chlamydia trachomatis and other sexually transmitted infections and subsequent ovarian cancer risk: results from the EPIC cohort. Int. J. Cancer 147, 2042–2052.

- Idahl A., Lundin E., Jurstrand M., Kumlin U., Elgh F., Ohlson N., et al.. (2011). Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium plasma antibodies in relation to epithelial ovarian tumors. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011:824627.

- Iverson-Cabral S. L., Astete S. G., Cohen C. R., Totten P. A. (2007). mgpB and mgpC sequence diversity in Mycoplasma genitalium is generated by segmental reciprocal recombination with repetitive chromosomal sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 66, 55–73.

- Iwuji C., Pillay D., Shamu P., Murire M., Nzenze S., Cox L. A., et al.. (2022). A systematic review of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Mycoplasma genitalium in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 77, 2074–2093.

- Jensen J. S., Cusini M., Gomberg M., Moi H., Wilson J., Unemo M. (2022). 2021 European guideline on the management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 36, 641–650.

- Jensen J. S., Fernandes P., Unemo M. (2014). In vitro activity of the new Fluoroketolide solithromycin (CEM-101) against macrolide-resistant and-susceptible Mycoplasma genitalium strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3151–3156.

- Jurstrand M., Jensen J. S., Magnuson A., Kamwendo F., Fredlund H. (2007). A serological study of the role of Mycoplasma genitalium in pelvic inflammatory disease and ectopic pregnancy. Sex. Transm. Infect. 83, 319–323.

- Kataoka S., Yamada T., Chou K., Nishida R., Morikawa M., Minami M., et al.. (2006). Association between preterm birth and vaginal colonization by mycoplasmas in early pregnancy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 51–55.

- Kayem G., Doloy A., Schmitz T., Chitrit Y., Bouhanna P., Carbonne B., et al.. (2018). Antibiotics for amniotic-fluid colonization by Ureaplasma and/or mycoplasma spp. to prevent preterm birth: a randomized trial. PLoS One 13:e0206290.

- Kim M. K., Shin S. J., Lee H. M., Choi H. S., Jeong J., Kim H., et al.. (2019). Mycoplasma infection promotes tumor progression via interaction of the mycoplasmal protein p37 and epithelial cell adhesion molecule in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 454, 44–52.

- Laumen J. G. E., van Alphen L. B., Maduna L. D., Hoffman C. M., Klausner J. D., Medina-Marino A., et al.. (2021). Molecular epidemiological analysis of Mycoplasma genitalium shows low prevalence of azithromycin resistance and a well-established epidemic in South Africa. Sex. Transm. Infect. 97, 152–156.

- Li C., Xl S., Ke-ying L., Jun H. (2022). Research progress of mycoplasma in tumor genesis and development. J. Pathogen Biol. 17, 356–360.

- Lillis R. A., Martin D. H., Nsuami M. J. (2019). Mycoplasma genitalium infections in women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic in New Orleans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 69, 459–465.

- Lis R., Rowhani-Rahbar A., Manhart L. E. (2015). Mycoplasma genitalium infection and female reproductive tract disease: a meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 61, 418–426.

- Liu X., Rong Z., Shou C. (2019). Mycoplasma hyorhinis infection promotes gastric cancer cell motility via beta-catenin signaling. Cancer Med. 8, 5301–5312.

- Lokken E. M., Balkus J. E., Kiarie J., Hughes J. P., Jaoko W., Totten P. A., et al.. (2017). Association of recent bacterial vaginosis with acquisition of Mycoplasma genitalium. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 194–201.

- Ma C., Du J., Dou Y., Chen R., Li Y., Zhao L., et al.. (2021). The associations of genital mycoplasmas with female infertility and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Sci. 28, 3013–3031.

- Machalek D. A., Tao Y., Shilling H., Jensen J. S., Unemo M., Murray G., et al.. (2020). Prevalence of mutations associated with resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones in Mycoplasma genitalium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 1302–1314.

- Macpherson I., Russell W. (1966). Transformations in hamster cells mediated by mycoplasmas. Nature 210, 1343–1345.

- Manhart L. E., Critchlow C. W., Holmes K. K., Dutro S. M., Eschenbach D. A., Stevens C. E., et al.. (2003). Mucopurulent cervicitis and Mycoplasma genitalium. J. Infect. Dis. 187, 650–657.

- Martin D. H., Manhart L. E., Workowski K. A. (2017). Mycoplasma genitalium from basic science to public health: summary of the results from a National Institute of allergy and infectious Disesases technical consultation and consensus recommendations for future research priorities. J. Infect. Dis. 216, S427–S430.

- Masha S. C., Cools P., Descheemaeker P., Reynders M., Sanders E. J., Vaneechoutte M. (2018). Urogenital pathogens, associated with trichomonas vaginalis, among pregnant women in Kilifi, Kenya: a nested case-control study. BMC Infect. Dis. 18:549.

- McGowin C. L., Annan R. S., Quayle A. J., Greene S. J., Ma L., Mancuso M. M., et al.. (2012). Persistent Mycoplasma genitalium infection of human endocervical epithelial cells elicits chronic inflammatory cytokine secretion. Infect. Immun. 80, 3842–3849.

- McGowin C. L., Popov V. L., Pyles R. B. (2009). Intracellular Mycoplasma genitalium infection of human vaginal and cervical epithelial cells elicits distinct patterns of inflammatory cytokine secretion and provides a possible survival niche against macrophage-mediated killing. BMC Microbiol. 9:139.

- McGowin C. L., Radtke A. L., Abraham K., Martin D. H., Herbst-Kralovetz M. (2013). Mycoplasma genitalium infection activates cellular host defense and inflammation pathways in a 3-dimensional human endocervical epithelial cell model. J. Infect. Dis. 207, 1857–1868.

- McGowin C. L., Spagnuolo R. A., Pyles R. B. (2010). Mycoplasma genitalium rapidly disseminates to the upper reproductive tracts and knees of female mice following vaginal inoculation. Infect. Immun. 78, 726–736.

- McGowin C. L., Totten P. A. (2017). The unique microbiology and molecular pathogenesis of Mycoplasma genitalium. J. Infect. Dis. 216, S382–S388.

- Moore K. R., Tomar M., Taylor B. D., Gygax S. E., Hilbert D. W., Baird D. D. (2021). Mycoplasma genitalium and bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria in a non-clinic-based sample of African American women. Sex. Transm. Dis. 48, 118–122.

- Namiki K., Goodison S., Porvasnik S., Allan R. W., Iczkowski K. A., Urbanek C., et al.. (2009). Persistent exposure to mycoplasma induces malignant transformation of human prostate cells. PLoS One 4:e6872.

- Napierala Mavedzenge S., Weiss H. A. (2009). Association of Mycoplasma genitalium and HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 23, 611–620.

- Nolskog P., Backhaus E., Nasic S., Enroth H. (2019). STI with Mycoplasma genitalium-more common than chlamydia trachomatis in patients attending youth clinics in Sweden. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38, 81–86.

- Noma I. H. Y., Shinobu-Mesquita C. S., Suehiro T. T., Morelli F., De Souza M. V. F., Damke E., et al.. (2021). Association of Righ-Risk Human Papillomavirus and Ureaplasma parvum co-infections with increased risk of low-grade squamous intraepithelial cervical lesions. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 22, 1239–1246.

- Nye M. B., Harris A. B., Pherson A. J., Cartwright C. P. (2020). Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium infection in women with bacterial vaginosis. BMC Womens Health 20:62.

- Oakeshott P., Aghaizu A., Hay P., Reid F., Kerry S., Atherton H., et al.. (2010). Is Mycoplasma genitalium in women the “new chlamydia?” A community-based prospective cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51, 1160–1166.

- Perry M. D., Jones S., Bertram A., de Salazar A., Barrientos-Duran A., Schiettekatte G., et al.. (2022). The prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium (MG) and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) at testing centers in Belgium, Germany, Spain, and the UK using the cobas TV/MG molecular assay. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 42, 43–52.

- Piao J., Lee E. J., Lee M. (2020). Association between pelvic inflammatory disease and risk of ovarian cancer: an updated meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 157, 542–548.

- Pineiro L., Idigoras P., Cilla G. (2019). Molecular typing of Mycoplasma genitalium-positive specimens discriminates between persistent and recurrent infections in cases of treatment failure and supports contact tracing. Microorganisms 7:609.

- Read T. R. H., Fairley C. K., Murray G. L., Jensen J. S., Danielewski J., Worthington K., et al.. (2019). Outcomes of resistance-guided sequential treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium infections: A prospective evaluation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 68, 554–560.

- Read T. R. H., Jensen J. S., Fairley C. K., Grant M., Danielewski J. A., Su J., et al.. (2018). Use of Pristinamycin for macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 328–335.

- Refaat B., Ashshi A. M., Batwa S. A., Ahmad J., Idris S., Kutbi S. Y., et al.. (2016). The prevalence of chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium tubal infections and their effects on the expression of IL-6 and leukaemia inhibitory factor in fallopian tubes with and without an ectopic pregnancy. Innate Immun. 22, 534–545.

- Rekha S., Nooren M., Kalyan S., Mohan M., Bharti M., Monika R., et al.. (2019). Occurrence of Mycoplasma genitalium in the peritoneal fluid of fertile and infertile women with detailed analysis among infertile women. Microb. Pathog. 129, 183–186.

- Rowlands S., Danielewski J. A., Tabrizi S. N., Walker S. P., Garland S. M. (2017). Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in midtrimester pregnancies using molecular microbiology. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 217, 71 e71–71 e75.

- Roxby A. C., Yuhas K., Farquhar C., Bosire R., Mbori-Ngacha D., Richardson B. A., et al.. (2019). Mycoplasma genitalium infection among HIV-infected pregnant African women and implications for mother-to-child transmission of HIV. AIDS 33, 2211–2217

- Roy A., Dadwal R., Yadav R., Singh P., Krishnamoorthi S., Dasgupta A., et al.. (2021). Association of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma species infection and organism load with cervicitis in north Indian population. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 73, 506–514.

- Sena A. C., Lee J. Y., Schwebke J., Philip S. S., Wiesenfeld H. C., Rompalo A. M., et al.. (2018). A silent epidemic: the prevalence, incidence and persistence of Mycoplasma genitalium among young, asymptomatic high-risk women in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 67, 73–79.

- Shilling H. S., Garland S. M., Costa A. M., Marceglia A., Fethers K., Danielewski J., et al.. (2022). Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence and associated factors among women presenting to a pregnancy termination and contraception clinic, 2009-2019. Sex. Transm. Infect. 98, 115–120.

- Shipitsyna E., Khusnutdinova T., Budilovskaya O., Krysanova A., Shalepo K., Savicheva A., et al.. (2020). Bacterial vaginosis-associated vaginal microbiota is an age-independent risk factor for chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium and Trichomonas vaginalis infections in low-risk women, St. Petersburg, Russia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39, 1221–1230.

- Shipitsyna E., Unemo M. (2020). A profile of the FDA-approved and CE/IVD-marked Aptima Mycoplasma genitalium assay (Hologic) and key priorities in the management of M. genitalium infections. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 20, 1063–1074.

- Soni S., Horner P., Rayment M., Pinto-Sander N., Naous N., Parkhouse A., et al.. (2019). British Association for Sexual Health and HIV national guideline for the management of infection with Mycoplasma genitalium (2018). Int. J. STD AIDS 30, 938–950.

- Stafford I. A., Hummel K., Dunn J. J., Muldrew K., Berra A., Kravitz E. S., et al.. (2021). Retrospective analysis of infection and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Mycoplasma genitalium among pregnant women in the southwestern USA. BMJ Open 11:e050475.

- Svenstrup H. F., Fedder J., Abraham-Peskir J., Birkelund S., Christiansen G. (2003). Mycoplasma genitalium attaches to human spermatozoa. Hum. Reprod. 18, 2103–2109.

- Sweeney E. L., Bradshaw C. S., Murray G. L., Whiley D. M. (2022). Individualised treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium infection-incorporation of fluoroquinolone resistance testing into clinical care. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, e267–e270.

- Sweeney E. L., Trembizki E., Bletchly C., Bradshaw C. S., Menon A., Francis F., et al.. (2019). Levels of Mycoplasma genitalium antimicrobial resistance differ by both region and gender in the State of Queensland, Australia: implications for treatment guidelines. J. Clin. Microbiol. 57:555.

- Taylor B. D., Zheng X., O’Connell C. M., Wiesenfeld H. C., Hillier S. L., Darville T. (2018). Risk factors for Mycoplasma genitalium endometritis and incident infection: a secondary data analysis of the T cell response against chlamydia (TRAC) study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 94, 414–420.

- Taylor-Robinson D., Jensen J. S. (2011). Mycoplasma genitalium: from Chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24, 498–514.

- Tovo S. F., Zohoncon T. M., Dabire A. M., Ilboudo R., Tiemtore R. Y., Obiri-Yeboah D., et al.. (2021). Molecular epidemiology of human papillomaviruses, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium among female sex Workers in Burkina Faso: prevalence, coinfections and drug resistance genes. Trop Med. Infect. Dis. 6:90.

- Trabert B., Waterboer T., Idahl A., Brenner N., Brinton L. A., Butt J., et al.. (2019). Antibodies against Chlamydia trachomatis and ovarian cancer risk in two independent populations. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 111, 129–136.

- Trent M., Coleman J. S., Hardick J., Perin J., Tabacco L., Huettner S., et al.. (2018). Clinical and sexual risk correlates of Mycoplasma genitalium in urban pregnant and non-pregnant young women: cross-sectional outcomes using the baseline data from the Women’s BioHealth study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 94, 411–413.

- Tully J. G., Taylor-Robinson D., Cole R. M., Rose D. L. (1981). A newly discovered mycoplasma in the human urogenital tract. Lancet 1, 1288–1291.

- Van Der Pol B., Waites K. B., Xiao L., Taylor S. N., Rao A., Nye M., et al.. (2020). Mycoplasma genitalium detection in urogenital specimens from symptomatic and asymptomatic men and women by use of the cobas TV/MG test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 58:2124.

- van der Schalk T. E., Braam J. F., Kusters J. G. (2020). Molecular basis of antimicrobial resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 55:105911.

- Van Dijck C., De Baetselier I., Cuylaerts V., Buyze J., Laumen J., Vuylsteke B., et al.. (2022). Gonococcal bacterial load in PrEP users with Mycoplasma genitalium coinfection. Int. J. STD AIDS 33, 129–135.

- Vodstrcil L. A., Plummer E. L., Doyle M., Murray G. L., Bodiyabadu K., Jensen J. S., et al.. (2022). Combination therapy for Mycoplasma genitalium, and new insights into the utility of parC mutant detection to improve cure. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, 813–823.

- Wang Y., Hong S., Mu J., Wang Y., Lea J., Kong B., et al.. (2019). Tubal origin of “ovarian” low-grade serous carcinoma: A gene expression profile study. J. Oncol. 2019:8659754.

- Wang R., Trent M. E., Bream J. H., Nilles T. L., Gaydos C. A., Carson K. A., et al.. (2022). Mycoplasma genitalium infection is not associated with genital tract inflammation among adolescent and young adult women in Baltimore, Maryland. Sex Transm. Dis. 49, 139–144.

- Workowski K. A., Bachmann L. H., Chan P. A., Johnston C. M., Muzny C. A., Park I., et al.. (2021). Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 70, 1–187.

- Yan X., Xiang H., Tao Y., Xu Z., Xuelong S., Jinyan Q., et al.. (2022). Mycoplasma genitalium infection rate among pregnancy females in China: a meta-analysis. Chin. J. Evid. Med. 22, 90–95.

- Ye H., Song T., Zeng X., Li L., Hou M., Xi M. (2018). Association between genital mycoplasmas infection and human papillomavirus infection, abnormal cervical cytopathology, and cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 297, 1377–1387.

- Yin Y. P., Li H. M., Xiang Z., Liang G. J., Shi M. Q., Zhou Y. J., et al.. (2013). Association of sexually transmitted infections with high-risk human papillomavirus types: a survey with 802 female sex workers in China. Sex. Transm. Dis. 40, 493–495.

- Oliphant J., Azariah S. (2013). Cervicitis: limited clinical utility for the detection of Mycoplasma genitalium in a cross-sectional study of women attending a New Zealand sexual health clinic. Sex. Health 10, 263–267.

- Olson E., Gupta K., Van Der Pol B., Galbraith J. W., Geisler W. M. (2021). Mycoplasma genitalium infection in women reporting dysuria: A pilot study and review of the literature. Int. J. STD AIDS 32, 1196–1203.

- Papathanasiou A., Djahanbakhch O., Saridogan E., Lyons R. A. (2008). The effect of interleukin-6 on ciliary beat frequency in the human fallopian tube. Fertil. Steril. 90, 391–394.

- Paton G. R., Jacobs J. P., Perkins F. T. (1965). Chromosome changes in human diploid-cell cultures infected with mycoplasma. Nature 207, 43–45.

- Payne M. S., Ireland D. J., Watts R., Nathan E. A., Furfaro L. L., Kemp M. W., et al.. (2016). Ureaplasma parvum genotype, combined vaginal colonisation with Candida albicans, and spontaneous preterm birth in an Australian cohort of pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16:312.